Link to:

- Raising the Caps – Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018

- Cap Exemptions: Emergencies, Disasters, Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO)

- Enforcing the Caps: Sequestration

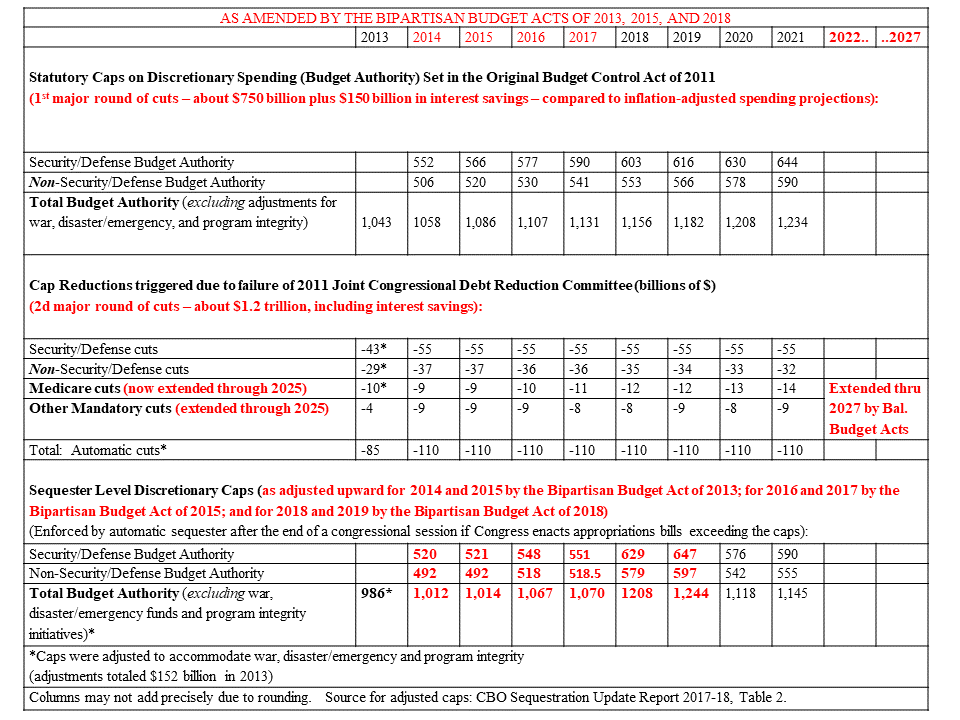

Discretionary Spending Caps (2011); Bipartisan Budget Acts of 2013, 2015, and 2018

Discretionary Spending

- The Federal Budget divides all spending into two broad categories. About 30% of federal spending is called “discretionary spending,” because the amount of spending flows from annual funding decisions by Congress’ Appropriations Committees.

- The other 70% of the budget is called “mandatory spending,” because the amount of outlays flow from legal obligations of the federal government established in law–mostly in the form of “entitlement” programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

- The 30% of the budget that is “discretionary” is about one-half funding for defense programs and one-half for non-defense programs.

- Discretionary spending is enacted annually by the Appropriations Committees through 12 regular appropriations bills — although sometimes the bills are packaged together into an “omnibus” measure.”

BCA of 2011 and Bipartisan Budget Acts of 2013, 2015, and 2018

- The Budget Control Act of 2011 (“BCA”) — negotiated during a lengthy political impasse over raising the debt ceiling – added a new layer of measures in the budget process aimed at reducing projected deficits. Tight statutory spending caps were imposed on total defense and non-defense discretionary spending for each year through FY 2021 to reduce deficits by more than $900 billion over 9 years (including interest reductions). The caps are enforced by automatic across-the-board budget cuts (“sequestration”) in appropriations bills if the caps are breached in any year.

- In addition, the BCA established a congressional “Super Committee” to achieve another $1.2 trillion in long-term deficit reduction through mandatory spending and tax reforms (including interest savings). However, because the Super Committee failed to agree on a long-term entitlement and tax reform package in the allotted time, additional budget cuts of $1.2 trillion over nine years went into effect in the form of further reductions in the annual discretionary spending caps for each year through FY ‘21.

- Subsequently, however, the automatic spending cuts for FY 2013, were delayed for two months and modestly reduced by the January 1, 2013 “Fiscal Cliff Agreement,” which also extended most of the expiring Bush tax cuts. (The anticipated expiration of the Bush tax cuts along with the January 2013 sequester had been dubbed a “fiscal cliff” that could cause another recession and generated a great deal of economic angst – eventually leading to the Fiscal Cliff Agreement.) Under the Fiscal Cliff Agreement, the modestly reduced FY ’13 spending cuts went into effect in the sequester of March 2013.

- The $1.2 trillion in additional discretionary spending cuts over nine years — triggered by the Super Committee’s failure – have been criticized because nearly the entire burden of this additional deficit reduction (more than 80%) was placed on discretionary spending – which is only one-third of the budget.

- The additional layer of cuts resulted in even tighter defense and nondefense discretionary caps for each year through 2021 – with levels that, in the view of many policymakers, did not adequately accommodate national security needs, annual inflation, a growing and aging population, necessary infrastructure growth and repairs, or rapidly growing veterans’ healthcare costs (which are funded by discretionary appropriations).

- Consequently, in late 2013, after political gridlock lead to a government shutdown in October, Congress and the White House agreed in the “Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013” to a two-year deal to increase the spending caps for FY 2014 and FY 2015.

- Two years later, in the fall of 2015, Congress and the Administration faced a nearly identical budget stand-off and again came to a similar agreement to increase the spending caps for FY 2016 and FY 2017 in the “Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015” (HR 1314, Public Law 114-74). The 2015 budget agreement increased total discretionary spending by $80 billion over the two-year period, plus an additional $32 billion in war funding. The budget law also avoided a debt crisis by suspending the federal debt ceiling through March 15, 2017.

- In early 2018, Congress passed the “Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018” that raised the statutory caps on discretionary spending by a total of $296 billion over FY 2018 and FY 2019 — increasing defense by 15% in each year, and increasing non-defense spending by 12% in FY 2018 and 13% in FY 2019. The Act also suspending the debt ceiling through March 1, 2019.

- It is likely that Congress and the Administration will negotiate another Bipartisan Budget Act for Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021 — the last two years of the BCA’s spending caps.

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 raised the statutory caps on discretionary spending by a total of $296 billion over FY’18 and FY’19.

- Defense caps:

- FY’18 increased from $549 billion to $629 billion (+$80 billion, 15%)

- FY”19 increased from $562 billion to $647 billion (+$85 billion, 15%)

- Non-Defense caps to increase $63 billion in FY ’18, and $68 billion in FY ’19.

- FY’18 increased from $516 billion to $579 billion (+$63 billion, 12%)

- FY’19 increased from $529 billion to $597 billion (+$68 billion, 13%)

The chart below displays the Statutory Spending Caps on Defense and Non-Defense Discretionary Spending as enacted by the Budget Control Act of 2011, and subsequently reduced (“sequestered”) by the inaction of the Joint Committee on Debt Reduction, and subsequently raised by the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015, and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018. (Source for update numbers: CBO Sequestration Report and BBA of 2018)